Beating uncertainty by scaling into trends

Look at the volume of any bar on a chart. You will notice that it is about the same on bars that, with hindsight, are obvious buy or sell signals. Casual observers might ask how that can be. Doesn’t everyone enter on these clear-cut setups? The reason volume stays consistent is that while individual traders watch for these traditional setups so they can use tight stops, institutions see setups every second of the day.

A chart is a representation of what is taking place in a market — where buyers and sellers come together to determine a fair price at which to buy or sell. Of course, buyers want to buy lower and sellers want to sell higher, but what constitutes high and low is not that clear.

As a result of this uncertainty, traders rarely are more than 60% sure of whether the next several ticks will be up or down. Probability is only high during strong breakouts, but these are rare. Usually, confusion reigns; as a trader, you have to learn to trade when you are not quite as confident as you would like to be.

New traders often think of a setup as a reversal bar or pattern. A broader definition of a setup is any reason to take a trade, and it is composed of context as well as a specific signal bar.

Context is simply all of the bars to the left of the bar in question. For example, when you are looking to buy, you want the market to be testing a support level, such as a prior low, a trendline, a measured move projection, a breakout point or a moving average. You then hope to see a signal setup such as a bull reversal bar. This indicates that the market is reversing up from that support, and it increases your confidence that buying above the high of that bar will result in a profitable trade.

That said, if you wait for these perfect setups, you will not take many trades. Also, you will miss many of them because of complacency and you’ll be unable to act when the setup forms. For example, there are 81 bars on the five-minute chart of an E-mini day session. If you are watching every tick for several hours and your setup has not formed, you naturally will begin to believe that it won’t form any time soon.

This mindset will make you unprepared to trade. Great setups usually happen quickly and unexpectedly, and rarely are clear until many bars later. Beginners invariably miss them because they always are searching for certainty.

Such an attitude demonstrates a misunderstanding of how markets work. There has to be someone taking the opposite side of your trade, and if your trade is such an obvious buy setup, there will not be anyone willing to sell to you. Even the best trades are less certain than you would like them to be. At the end of the day when you print out a chart, the setup is clear, but that is because you now can see all of the bars to the right. In real time, you only see the bars to the left of your setup and signals are far less certain.

One way to handle this uncertainty is to scale into trades.

Assets at risk

Scaling into a trade is directly related to how much you risk on any given position. Determining your position size is based on a combination of factors, including the market you’re trading, current volatility, trading strategy, your other investments, net worth, penchant for risk and desire for reward. However, a good rule of thumb is a relatively simple one. Trade the “I don’t care” size. In other words, trade a position size that is so small that you don’t care much if you lose. This will allow a much better chance at remaining objective and doing the right thing. Invariably, beginners tend to enter and exit either too early or too late, and their decisions usually are prompted by emotion.

The I don’t care size is much smaller than what most traders risk. For most, this is less than 2% or so of their total risk capital on any trade. If you think you can comfortably trade 10 E-minis, then you probably should trade only two or three. If you think that you can trade 1,000 SPY shares, you probably should trade only 200 or 300.

A trader might ask, “How do you expect me to get rich if I trade so small?” The answer is simple. One of the first steps to getting rich is to remain objective, and you need to trade small so you can do what the market is telling you to do, not what your anxiety and greed are making you do.

Markets and sizing

If a trader is new to scaling into a position and wants to minimize the total dollars at risk, a reasonable alternative to trading the E-mini or the SPY is to trade weekly SPY options. For example, if a trader wanted to scale into a long position, he or she might buy one at-the-money (ATM) call. If a call is purchased on Monday, it has five days to expiration and it might cost 0.90, or $90. If a trader bought the call on Friday, the day it expires, it might cost $30. Even if that $30 call expired worthless at the end of the day, the total loss would be $30 plus about $1 in commissions.

The weekly SPY options are liquid and the bid-ask spread of the ATM call usually is a penny. There are many trades every day of 1,000 or more calls. Trades of 5,000 or more also are common. An individual trader does not have to worry about getting too big for this market.

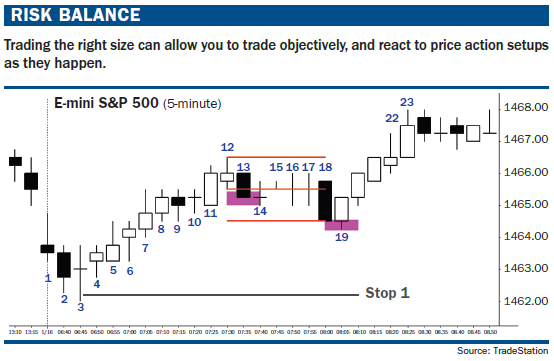

For the sake of the example in “Risk balance” (below), assume that a trader comfortably can trade 10 E-mini contracts and is willing to risk two points per contract. That means he’s willing to risk $1,000 (plus about $50 in commissions) on each trade. The five-minute chart has 81 bars during the trading session, and the numbering reflects this (for example, bar 12 is the 12th bar of the day). The market reversed up at bar 3, and bar 7 was a small breakout because its close was above the high of the prior bar, creating an intraday gap. Gaps like this are important because they are a sign of strength, and automated trading systems often treat them as measuring gaps and look to take profits at a measured move up.

By the close of bar 8, most traders assumed that the market was going higher, even if there was a pullback. The predominant assumption is that any pullback would remain above the bar 3 low where the trend began. At this point, the market was “always in long,” which means if a trader had to take a trade at this moment, long or short, only long trades would be considered. Bulls are buying for every conceivable reason, and many have limit orders below the current market price to add on or to get long on any pullback.

Assume that our trader finally decided on the high of bar 12 that the market was going higher and he bought them, which turned out to be the worst price. If he is comfortable risking $1,000 in the E-mini, how big a position should he take? It depends on the game plan, for example, if the trader is going to scale in on a pullback before the market reaches whatever profit target he has. At the moment, the trader believes the market is going higher as long as it stays above the bar 3 low. This is because a bull trend has higher lows and pullbacks need to stay above the most recent higher low. The trader then puts in a protective stop at one tick below the bar 3 low, risking 4.75 points, or about $240 per contract.

One approach is to buy four contracts. This would keep risk to about $1,000. Our trader is confident in the profit potential and therefore believes that the probability is at least 60%. Given this, reward must be at least equal to the actual risk. (When success is less certain, which is most of the time, traders should target a reward that is at least twice their current risk.) Once the market reached a new high at bar 22, the trader would raise the stop to below bar 19, the most recent higher low, and a profit equal to the actual risk would be necessary. The trader now knows that the actual number of ticks to risk to stay in the trade was to one tick below bar 19, which was 10 ticks or 2.5 points.

The scale effect

The trader’s equation is the basis of every trade that all successful traders take (see “The trader’s equation: Should I take this trade?” March 2011). The probability of success (here 60%) multiplied by the profit target (yet to be determined) must be at least as big as the chance of a loss (here 40%) times the actual risk (here 2.5 points).

Because the trader needs a reward at least as big as the risk, part or all of the trade could be exited at 2.5 points above the entry price. This is the profit target. Although not shown in the chart, the high of the day was exactly at this goal, which likely means that a lot of computers employed this same calculation to take profits here.

An alternative approach is to scale in lower. Experienced traders would recognize that the rally to the bar 12 high was not strong. There were no consecutive big bull trend bars; most of the bodies were small, the tails were prominent and there was a lot of overlap between adjacent bars. This suggests that even though a second leg up was likely, so was a pullback. The day probably would be either a trading-range day or a broad bull channel, both of which have pullbacks. With that in mind, a trader might have bought only a small position at the bar 12 high just to capture part of the trend in case the market continued higher without pulling back. The plan would be to add on if the market pulled back after entry, which it did.

There are many ways to structure a scale program, but the common element is to maintain an exit plan. In “Risk balance” this came into play if the market fell below the bar 3 low. As long as a trader structured a trade so total loss was under $1,000, or 20 points if the stop was hit, and the profit was as big as the actual risk, the plan would be mathematically sound.

Price action scaling

Say the trader bought one contract at the bar 12 high and was willing to add at one-point intervals down to the stop below bar 3, which is 4.5 points lower. The trader would be risking 4.75 points on his first entry, 3.75 on his second, 2.75 on his third, 1.75 on his fourth and 0.75 on his fifth. If the stop were hit, the total loss would be 13.75 points, or about $700, and is less than the maximum allowable loss.

Most individual traders would not want five separate entries in a trade and would stop after adding one or two times. If the trader would have added on at one and two points down, fills would have been on bars 13 and 19 and total risk would have been 11.75 points. The trade would have achieved an 11.75-point profit later in the day; or, the trader could have exited the entire position once the market returned to the original entry price at the bar 12 high, which is what many successful traders do. This is one reason markets often pull back at new highs — bulls use them to take profits.

Another approach would be not to buy the high of bar 12 and simply wait to buy a one- or two-point pullback and add on one or two points lower, with a position size that would keep the total risk to under $1,000. The expected reward could have been at least as much as the risk, but many exit at their first entry price.

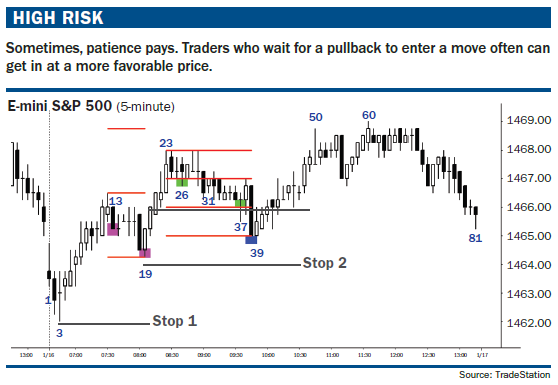

This process can be repeated. Say a trader was eager to get long and bought the exact high at bar 23 in “High risk” (below). The stop would be one tick below the bar 19 low, which was 3.75 points down, so his risk would be four points. If he planned to scale in one point below, and at every additional one point lower, he would have been filled on bars 26 and 37 in the green boxes. Although the bar 39 low was three points down, the limit order probably would not have been filled; the market usually has to fall a tick below a buy limit order for a fill.

Alternatively, the trader could have planned on a pullback and waited to take his first entry at two points below the bar 23 high. The fill would have been on bar 37. The trader then could plan not to scale in and simply place a stop below the bar 19 low. Because risk was two points, five contracts could be purchased.

The trader also could plan to add on a bigger position lower, as long as total risk remained below the $1,000 (20-point) maximum. For example, if four contracts were bought on a two-point pullback, he could buy eight more contracts one point lower. Risk would be to below the bar 19 low. This would be two points of risk times four contracts from initial entry, and one point times eight contracts on the second entry, for a total risk of 16 points; this is below the maximum to be risked on any trade.

The trader could then hold for a profit of 16 points. Because the position is 14 contracts, he could exit at just one point above the average entry price. Alternatively, half the position could be exited there and the other half at a new high. Many traders obviously had this idea, creating the reversal at the bar 50 high. Our trader is confident in the profit potential and therefore believes that the probability is at least 60%.

This is based on an article from the May 2013 issue issue of Futures magazine.